Testing FBI-endorsed forensic DNA kit in Canada's genetic melting pot

UTM forensic scientists are studying the accuracy of a forensic DNA kit in predicting an individual's hair and eye colour. What makes this study novel is that the researchers are testing the commercially-prepared kit on a population of individuals of mixed ancestry.

"My student is trying to evaluate whether or not how individuals self-declare their ancestry is consistent with what the genetic information is predicting they look like," says Nicole Novroski, an assistant professor of forensic science in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Toronto Mississauga. Novroski researches human identity in relation to forensic and investigative genetics and develops novel forensic genetic techniques.

DNA profiling for investigative purposes

A current DNA profile relies on repeating segments of a person's genome known as short-tandem repeats (STRs). STR typing in forensic biology has become the "gold standard," Novroski says. Now, with improved chemistry and technology, researchers can explore new areas in the genome to capture additional information such as ancestry and phenotype characteristics, which include hair and eye colour.

These new ancestry and phenotype markers are already used in some jurisdictions to develop investigative leads about a suspect, a victim or a missing person, but they are not currently used in court, Novroski says. However, Verogen’s ForenSeq DNA Signature Prep Kit under study in Novroski's lab has received National DNA Index System (NDIS) approval. "Meaning that the FBI has endorsed the use of this kit in forensic laboratories for traditional DNA profiling purposes."

The ForenSeq kit allows scientists to test for both the traditional DNA markers as well as these new phenotype and ancestry markers which makes the kit both unique and valuable. Novroski says that the phenotype and ancestry information from Shadoff's study will contribute to the forensic community's understanding of both the power and limitations of exploring new genetic markers in forensic applications.

Fourth year forensic biology student Rachel Shadoff is collecting the DNA samples for the study from volunteers of mixed DNA ancestry.

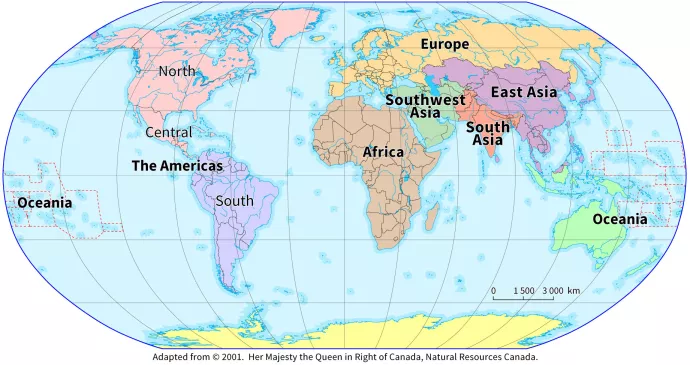

"I am looking for a very specific set of people," says Shadoff. Her ideal volunteer is the first generation child of genetic mixing from two distinct ancestral populations. "If we had someone who was, let's say, European and African, that would work very well because those populations are genetically very distinct. Southwest Asia and somewhere in the Americas, Oceania or East Asia–all those combinations or different types of those combinations would work."

Volunteers provide either a blood sample through a finger-prick or a saliva sample through a cheek swab. They also complete a survey to self-identify their hair colour, eye colour, their biological sex and the population or populations they are from.

"And that's it. We do not collect your name, student number or any kind of identifying information with the sample. Everybody is anonymous," says Shadoff.

Shadoff then prepares the samples using the kit, runs the samples through a DNA sequencing machine and analyzes the data.

One outcome of the study may be that the kit does not work for samples of mixed ancestry. That means the current markers used to assess hair and eye colour aren't good enough, Shadoff says. "This would potentially open up an area of study of which markers are better. And, if it does work, that's important, too. It lets us know that this is yet another type of population this kit works in and that it might be okay to use it in a forensic context."

Novroski says that while DNA studies are important, this study is particularly important for understanding the value of using predictive genetic tests to infer what an individual might look like or what an individual's ancestry might be when using the information for investigative purposes.

"If this study demonstrates that the genetics do not model how a person self-declares or what a person looks like, this DNA information needs to be used with caution. The test could implicate the wrong individual. Or, it could exclude a potentially viable suspect and that could impact future crime," she says.

Canada's rich genetic diversity

Analysis of the forensic DNA kit is just one of several studies in Novroski's lab. Her forensic genetics group is working with Canadian forensic biology government agencies and the Scientific Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods (SWGDAM) to generate new forensic biology datasets to better reflect Canada's current populations. "If you think about Canada's population of 30 years ago, it's very different from the population of today," she says.

Novroski also conducts experiments on the mitochondrial genome and its ties to ancestry and lineage studies, the intricacies and complications of DNA mixtures, the use of new collection devices for improved DNA yield, and on DNA transfer between surfaces. “These are big areas of interest in forensic genetics, and ultimately important to society.”

Canada is a melting pot of diversity and Novroski says it is vital to know if these forensic kits are precise, reliable and useful in an area like Toronto where its rich ethnic diversity also exists at the genetic level. "There is tremendous promise for this application in missing persons and unidentified remains cases. The goal of Rachel's study is to assess in which populations ancestry and phenotyping marker sets work best."

Revised for clarity: January 6, 2020 at 4:50 pm