Pandemic restrictions don’t hamper innovation, UTM economist’s research from the 1918 flu shows

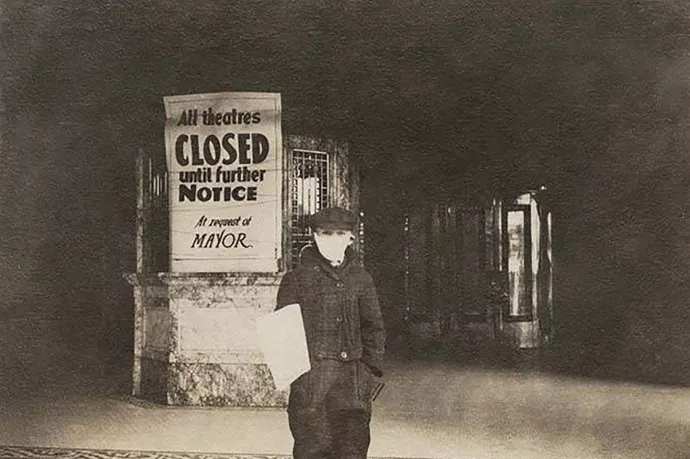

New research from the 1918 pandemic shows that bans on public gatherings and school closures didn't slow innovation, providing clues about the outcome of the most recent global health emergency.

As lockdowns descended on regions around the world in 2020 to limit the spread of COVID-19, economist Ruben Gaetani and his co-authors were curious whether there was any validity to concerns that strict rules on social gathering would put a crimp on local innovation. They used their enforced physical isolation to pull data from the 1918 flu pandemic, comparing patenting records to information about public health restrictions in 50 large U.S. cities.

“We expected to observe that longer restrictions would lead to lower invention rates,” says Gaetani, a professor of strategic management at U of T Mississauga, cross-appointed to Rotman School of Management. “After digging in our data, we found evidence that was opposite to that.”

Of the 50 cities studied, 17 experienced longer-than-average restrictions — such as school closures and bans on public gatherings — that totalled more than 90 days over the 1918 flu pandemic’s multiple waves. But patenting rates for those cities were generally six to nine per cent higher than rates for cities with shorter restrictions. The numbers were even higher looking specifically at what happened once the flu pandemic was over — seven to 12 per cent greater in the aftermath.

Researchers reason that cities where restrictions were in force longer created certainty, preserving an important ingredient in the innovation process, which requires an investment of time, resources and knowledge acquisition.

“Uncertainty makes people less willing to carry out this investment because it makes returns less predictable,” says Gaetani. “Longer restrictions favoured a co-ordinated and resolute response to the pandemic which anchored expectations and reduced uncertainty.”

There were differences, of course, between the two public health events. The 1918 flu was shorter and more intense, its main waves running between the spring of 1918 until April 1919 with the fall’s second wave being the most severe and the period when public health restrictions were imposed.

The COVID-19 pandemic, lasting more than three years, had much longer-running and more extensive restrictions. Innovators during this most recent pandemic, however, would have had the advantage of virtual communication technologies that allowed them to continue collaborating with other people.

Those differences make it hard to say how much the findings might predict innovation behaviour during COVID-19 or whether longer social restrictions are ultimately better for innovation in such an emergency than shorter ones.

“Our findings suggest that there are other channels beyond the restrictions to local interactions that should be taken into account,” when looking at a public health emergency’s impact on the innovation process and the economy, says Gaetani.

The research was co-authored with Enrico Berkes of the University of Maryland — Baltimore County, Oliver Deschenes of UC Santa Barbara, and Jeffrey Lin and Christopher Severen, both of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. There is early online access to the study, which is forthcoming in The Review of Economics and Statistics.