The origin of Grant’s Atlas

Part three of a three-part series on the 70th anniversary of the Master of Biomedical Communications program

Coincident with its 70th anniversary, the biomedical communications program is involved with a project that unites its earliest work with its most recent. One of the initiatives that closes this loop arises out of an unexpected consequence of a world at war.

Before the Second World War, Germany dominated the global market for medical illustration books. When the German references became inaccessible, a University of Toronto professor named John Charles Boileau Grant stepped into the void, creating in short order a new atlas of anatomy.

“The atlas he proposed was also a reconception of how anatomy should be taught,” says Wooldridge. “The German atlases taught anatomy systemically: Here’s a musculoskeletal system, here’s the circulatory system, here’s the respiratory system and here’s the nervous system. But that’s not how you learn anatomy in the dissection lab. You see all of those things together.”

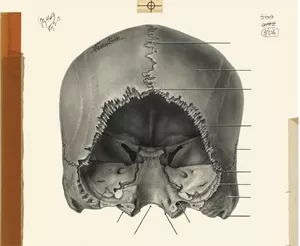

Grant’s Atlas remains a definitive reference for medical students. Various attempts have been made to enhance the original illustrations over the decades, but only now does there exist the technology and resources to completely modernize them.

“We created a high-resolution digital archive some years ago,” says Woolridge. “We just recently embarked on a project to remaster these amazing illustrations in colour.”

A project team is also digitally removing the labels and notes that have been added to the images over time. The illustrations can then be custom annotated in any language, and with the most current terminology.

“We try to maintain relevance to what’s happening out in the world,” says Woolridge. These days, that can mean anything from molecular reactions to big data analysis.

“I’m involved with a project at Sunnybrook looking at creating mobile apps that allow people with mood disorders to collect information about their mood over time,” he says. If you can start to make correlations between life events and changes in your mood overtime, then we think that people might be able to manage their illness more effectively.”

Read Part I of this series, "70 Years of visual communications" here >

Read Part 2 of this series, "Working for a greater good," here >