Good Versus Evil: Bacteria edition

An innovative strategy to tackle water-borne diseases common in the developing world has won a University of Toronto Mississauga professor a $100,000 grant from Grand Challenges Canada.

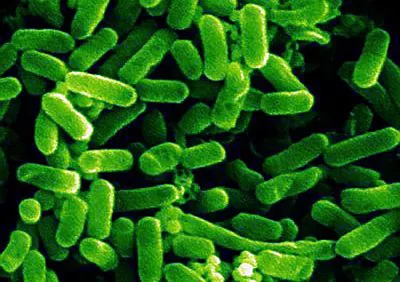

Associate Professor David McMillen, the associate chair of the Department of Chemical & Physical Sciences, received the financial award last month for his efforts to engineer bacteria that can fight diseases such as cholera, typhoid, dysentery and E. coli, which are primarily contracted by ingesting contaminated water or food. While still under development, McMillen says these disease-fighting bacteria could be a practical treatment method for health professionals in Asia, Africa and other regions hard hit by these illnesses, which, according to the World Health Organization, kill 2.2 million people each year. Grand Challenges Canada is a federally funded program that supports international and national initiatives aimed at improving global health.

“Synthetic biology has a lot of potential for this kind of work, and this is something I’ve been interested in for a long time, so it’s exciting for me to move in this direction of applied research,” said McMillen, who is working on the project in partnership with a doctor in the Philippines. “The biggest appeal is that it could allow people in these countries to do local productions [of the bacteria], providing a manageable solution to their problems.”

Millen’s research at UTM has historically focused on studying microorganisms such as bacteria and yeast to better understand their cellular processes, and designing new cellular devices to control their behaviour. He realized the real-world uses for his work while traveling with his wife in the Philippines, and learning about the country’s frequent outbreaks of typhoid and cholera. He also discovered that infection-related diarrhea causes 8.5 per cent of all deaths in Southeast Asia.

“We know how to do sanitation, but it’s being addressed very slowly in many parts of the world. What continues to be lacking are safe, chlorinated water supplies,” he says.

McMillen’s disease-targeting bacteria would sit dormant in the intestine, and be able to detect the chemical signals emitted by pathogens. They would then rupture and churn out bacteriophages—viruses programmed to attack the harmful invaders. Built into the bacteria would be safety mechanisms to regulate their numbers and destroy them once they are excreted from the body.

A key advantage of this approach is the bacteria are easy and cheap to make—they can be grown in milk, broth, yogurt or any other food source containing sugar and carbon dioxide. Once produced, they could be stored and deployed as needed to treat those affected. McMillen explains the core science behind the initiative and its potential health benefits in a YouTube video he created for his application for the Grand Challenges Canada grant.

One of 102 projects chosen from among 436 applications, and one of just 43 granted to Canadian researchers, the award is meant to sustain McMillen’s research over the next 18 months. The funding will be used to support fieldwork in the Philippines to examine microbes in water supplies, and to hire a doctoral fellow to assist with McMillen’s research. The next steps are to create a prototype of an engineered bacteriophage and, eventually, to conduct clinical trials, all of which could take upwards of a decade before the idea translates into a viable treatment for use in developing nations.

“It’s a long-term process, but we are laying the groundwork for future progress,” McMillen says. “This has a lot of potential to make a difference in how we address these infectious diseases worldwide.”