Violence and greed: UTM history and biology professors join forces to study Columbus’s impact

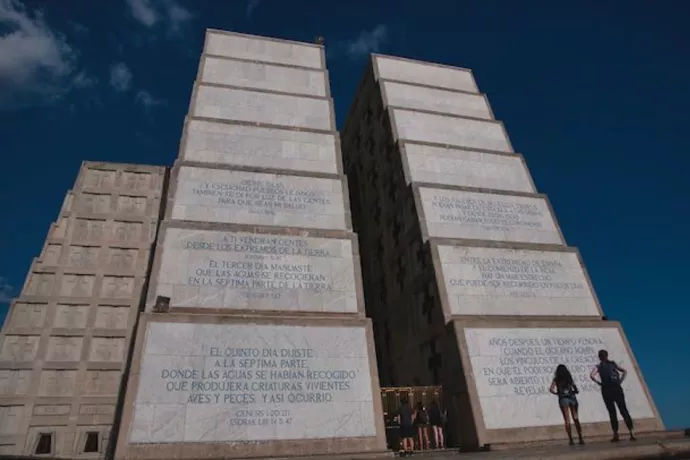

When UTM students first saw the Columbus Lighthouse in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic in 2019, they didn’t know quite what to say.

Standing before them was a giant concrete monument shaped like a cross, with beams of light that can project so brightly into the sky that they can be seen all the way to Puerto Rico.

“It's probably the biggest monument to Christopher Columbus in the world, and it’s so offensive in so many ways,” explains Mairi Cowan, a professor at UTM’s Department of Historical Studies. “It takes no account of human suffering or ecological devastation wrought by early modern colonialism.”

The Faro a Colón, known in English as the Columbus Lighthouse, was unveiled in Santo Domingo in 1992 – marking the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage across the Atlantic. The monument, which was built at an estimated cost of between $70 million and $250 million 1992 USD, is also purported to house Columbus’s remains, although authorities in Spain claim that the remains are in the Seville cathedral.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, students visited the site as part of an optional study-abroad component of the interdisciplinary course Across the Atlantic and Back: A History and Ecology of Exploration, Conquest, and Exchange from 1492 to Now. It initially started as a second-year seminar, and Cowan and her colleague Christoph Richter, a UTM biology professor, co-teach the course which is now going into its third year as a joint history and biology class with the new title Worlds Colliding: The History and Ecology of Exploration, Contact, and Exchange.

The students’ reaction inspired the professors to co-author a research paper that was recently published in the May 2021 issue of the historical flagship journal, The Public Historian.

Their paper, The Faro a Colón in Santo Domingo: Reinterpreting a “More Nearly Perfect” Memorial to Christopher Columbus, argues that the monument as originally designed is badly misaligned with the historical record, but that it can be reinterpreted to show the violence and greed of colonization.

“I couldn’t let the offense of it just go unspoken,” says Cowan. “We wanted to write something about how this monument can be taught responsibly and how, in spite of itself, it actually is a really good memorial to Columbus – but not as the designers meant it. There is a way to interpret it in a way that honours the real historical and ecological record of colonization.”

Richter describes how the ecological impact started when species such as pigs, wheat and different plants were brought into new ecosystems.

In a way, he says, introducing such animal and plant species is another reflection of the violence and greed of colonization.

“There were exchanges of microbes, plants and animals that ended up on either side of the Atlantic,” he says. “Those became invasive species, and you could see that as violence. It definitely changed the ecology of the island, if not the whole area. There's no question about it.”

Cowan and Richter’s class, which inspired the research paper, focuses on how our world has been shaped by the exchange of plants, animals and microbes between the Americas and Afro-Eurasia in the wake of Columbus’s first voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1492. Students examine changes to the world’s histories and ecologies, and consider how these changes created global systems and ecological challenges that still exist today.

The optional study abroad component allows students to experience first-hand effects of Columbus’ voyage in 1492, and the impact on today’s cultural and ecological realities in the Dominican Republic.

The professors describe how the students get a fuller understanding of ecological impacts when they drive through the countryside and visit the national botanical garden in Santo Domingo, where they learn about plants that are now endangered in the Dominican Republic.

“As we move through the country, (students) also see how this challenge is exacerbated by the poverty on the island,” Cowan explains. “People need to live. They need to grow food. They don't have water out of taps that they can drink. They're facing really difficult circumstances.

It's humbling to go to the country and not be on the resorts - but rather, be with Dominican people and see how they have to live in this country now. And it's been part of the Columbian exchange for more than 500 years.”

Richter adds that history and ecology are both interconnected when examining Columbus’s lasting impact.

“Where things become really interesting is when we actually link both, when we examine how historical events were influenced by the ecology, and how ecology was severely impacted and changed by historical events,” he says. “That's where we bring both of them together.”