UTM climate expert's new study underscores need to protect 'oasis of the Arctic'

Amidst the vast frozen and barren terrain of the Arctic is a unique marine ecosystem supporting a web of diverse natural life that, according to a new study by scientist Kent Moore, is managing to sustain itself against the impacts of climate change — so far.

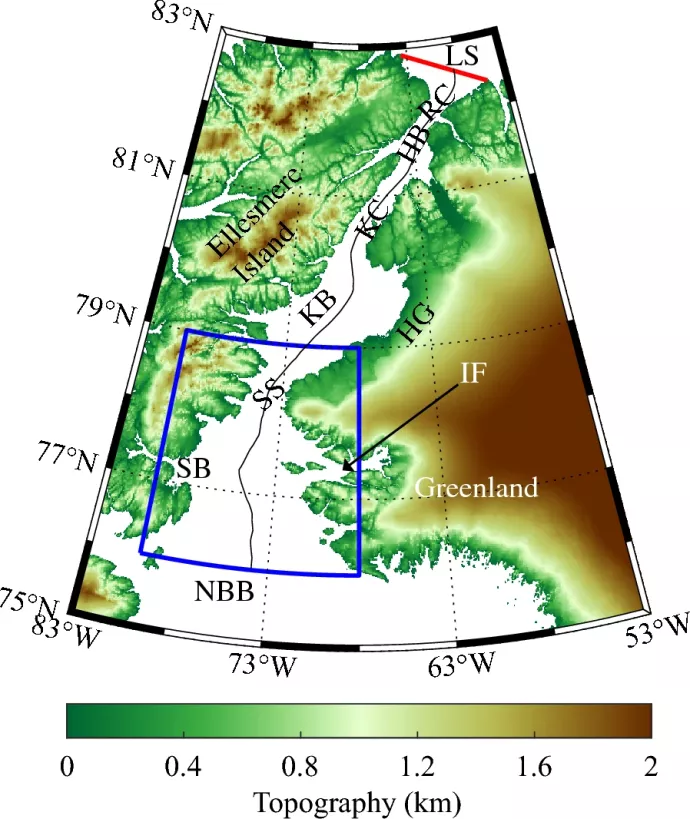

A professor of atmospheric physics at the University of Toronto Mississauga, Moore is studying an 85-000-square-foot expanse known as a polynya — the name for a year-round open-water area surrounded by sea ice. Located in north Baffin Bay between Canada and Greenland, it creates a relatively warmer microclimate with melted freshwater, which triggers an abundant bloom of phytoplankton each spring.

The site attracts diverse species of fish, birds, walruses, narwhals, whales, seals and polar bears who come to feed, mate and rest. For several millennia, the polynya has also been a source of traditional food for local Indigenous peoples.

Scientists refer to this site as the North Water (NOW) polynya, while Canada’s Inuit call it Sarvarjuac and among the Inuit of Greenland, it is known as Pikialasorsuaq. Whatever name you use, Moore wants you to understand its ecological importance.

“The Arctic is mostly like a desert,” Moore said. It's difficult for a lot of wildlife to survive. “But the North Water is quite amazing, because it’s the most biologically productive ecosystem in the region…You can think of it as an oasis in the Arctic,” he said.

The NOW is below the Nares Strait, a 40-kilometre by 600-kilometre waterway separating northwest Greenland from Ellesmere Island surrounded by the oldest and thickest sea ice in the world. Each winter, ice arches up to 100 kilometres in length form along the northern and southern ends of the strait. They stabilize the ice for seven or eight months, preventing any breaking ice floes from traveling down into the NOW.

To understand how the warming earth is affecting the region, Moore joined with two scientists from Environment and Climate Change Canada to study the ice arches. Their 2021 study found that thinning ice is causing these arches to collapse earlier and earlier each year.

“There’s been a lot of work suggesting that without the arches, the NOW will dramatically change,” Moore said. “That change would mean a reduction in productivity, less species in the region and just a general decline in the richness of the ecosystem.”

Recently, Moore partnered again with the same two scientists to examine satellite data showing patterns of ice arch formation and disintegration each winter since 2007. They also developed weather prediction models to estimate how, in the absence of ice arches, winds will blow ice downstream into the NOW.

They found that when arches do not form, the presence of sea ice tends to be about 10 per cent higher than usual. However, despite variations in ice arch activity, biological productivity in the NOW has held steady. Moore said this may be because the region’s strong winds push the ice into — and then out — of the polynya, leaving them no time to disturb the ecosystem. Their findings published in the journal Nature this month.

“It’s kind of a good news story, that the polynya appears to be more stable than people thought,” Moore said. “We can breathe a bit easier about the NOW for the next few years.”

But as climate change intensifies, Moore said, the NOW could be at risk. As a critical habitat for so many diverse species, and a key contributor to the food security of nearby Indigenous communities, he said we need to keep an eye on it.

“The underlying issue is that we’re still warming the planet up. And there are many other stresses on the environment and the animals in that region,” he said. “If you go to a scenario where we lose all the ice in the Arctic, then the NOW won’t be there anymore.”