New book explores how currency defined relationship between government and Indigenous communities in Canada

From beaver pelts to dollar bills, a new book by U of T Mississauga historian Brian Gettler offers an intriguing look at the complex relationship between physical currency and the state and First Nations people in early Canada.

“This isn’t a book about accounting,” says Gettler. “My interest has to do with how we create nation states through story, and how countries like Canada or the United States are born of colonialism.”

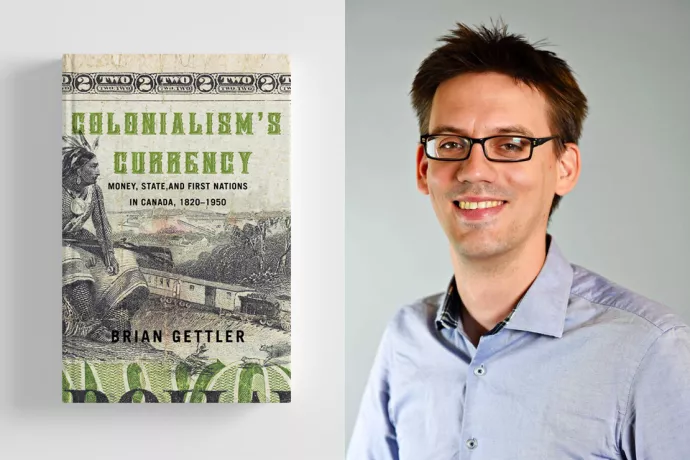

Published in July, Colonialism’s Currency: Money, State, and First Nations in Canada, 1820-1950 traces how currency systems have both symbolized and influenced interactions between the government and First Nations people over a 130 year period. Using documents from government, corporate and Indigenous community archives, Gettler’s research also reveals a great deal about the long-held racialized paternalistic notions about government oversight of Indigenous financial management that persist to this day.

“Money is one of the key ways in which the Canadian nation state expands over the 19th and 20th centuries,” says Gettler, who takes up the historic money trail with ‘made beaver’ tokens used by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) to pay Indigenous fur traders before the introduction of official common currency. The tokens would eventually be used as credits that could be exchanged for goods from the HBC trading post store before being replaced by a common currency system introduced by the government.

The government’s contentious and controlling relationship with Indigenous people is established symbolically on the country’s first currency, which is featured on the cover of Gettler’s book. The two-dollar Dominion of Canada bill, printed in 1870, features an Indigenous man in the foreground looking over a vista of gambolling livestock, a steam train and a city on the horizon.

According to Gettler, the currency design captures the massive changes wrought by colonialization and what it will mean for Indigenous people. “The Indigenous man holds a stem pipe and a gun pointed in the opposite direction, and he's just observing, from this little patch of wooded area, the developments in the progress of Canada,” says the historian. “All of these things suggest that Canada is going to grow and fill all of this land, and it's going to bring progress with it, and that Indigenous peoples will pass away before it.”

Gettler continues the story of what money symbolizes and how it moves between the state and Indigenous people through three case studies of three First Nations communities: the Wendat of Quebec; the Innu of Mashteuiatsh in central Quebec; and the Moose Factory Cree reserve in northern Ontario.

“I wanted to include communities that had different historical experiences of colonialism,” he says. The communities represent a sampling of interactions between First Nations people and the state, from the Wendat, who have a centuries-long relationship with nearby Quebec City, the newer Mashteuiatsh reserve, which has close economic ties to the town of Roberval, Quebec; and remote Moose Factory, which was secluded from the outside world until the 1930s.

Gettler’s research also reveals the development of ongoing government meddling in Indigenous financial matters by tightly controlling the cash flow for goods and services and funding. Such financial interference, Gettler notes, is not evident in white settler communities.

Gettler wraps his survey by revisiting the fur trade in the mid 20th century. When the Canadian government assumed control of the beaver pelt system in the 1930s and 40s, Indigenous trappers were suddenly forced to sign agreements and wait—often months—for payment in installments, rather than lump sums.

“This ‘reserving currency’ is the state's attempt to keep money out of the hands of Indigenous people,” Gettler says. “Under the Hudson’s Bay Company, they were not totally free, but they were at least getting credit immediately.”

“There's an assumption that ‘we have to go slow, we can't give too many responsibilities to First Nations, and we'll hire third-party accounting firms from big cities, because Indigenous people are clearly not spending their money correctly,’” he continues, adding that the approach has been “baked in” to government policies and laws that prevent Indigenous people from controlling their own destinies.

Looking backwards can help with the future, he says, noting that his book aimed at scholars of Indigenous history has also sparked interest from activists and advocates for Indigenous rights, and lawyers working in land claims law. “It’s one of the strange things about this particular field of history,” Gettler says. “Thinking about the state and thinking about capitalism in relation to First Nations remains current and necessary.”

Colonialism’s Currency: Money, State, and First Nations in Canada, 1820-1950 is published by McGill-Queen’s University Press.