Eliminating excessive force: UTM professor’s training techniques improve police performance

SWAT team officers prowled the school’s hallways, looking for the shooter who had left several dead. Highly alert, these officers bristled at every sound and movement around them.

The training exercise was going by the book until a child who should have been evacuated with her classmates suddenly appeared in the hallway. Instantly, the guns trained on her terrified face.

That distraction led to one mistake. In a real-world scenario, it easily could have been fatal.

Research has found that the stress police officers feel during these unpredictable, challenging and high-pressure situations can lead to cognitive difficulties, panic and lapses in judgment, raising the risk that an innocent bystander or a suspect will be hurt. To reduce lethal force errors, U of T Mississauga’s Judith Andersen has developed science-based use-of-force and

de-escalation training that includes techniques to help officers control how they react to stress and improve their split-second decisions when in the field.

“The reason people can’t de-escalate appropriately or be as effective on the job is highly related to stress response and the ability to modulate that response,” Andersen says. “It’s normal to react to stress. You need to learn how to tap into that.”

Even the most seasoned officers are not immune to their bodies’ biological signals, the psychology professor has learned in years of study in the field.

To conduct her work, Andersen fits heart-rate monitors to police officers who are run through what she describes as “highly realistic” simulations and real-world encounters. After each session, the trainees are asked to report their level of stress. In some cases, the trainees gape in disbelief when they watch videos of their reactions – yelling they did not hear and aggressive pointing gestures they did not realize they were making.

Andersen’s methods are already part of standard police training in Finland. She says she would like to see that training replicated elsewhere, including Ontario.

Changing the focus of police training in Ontario is long overdue, agrees Peter Shipley (BPHE 1987), who is chief instructor for the Strategic Research unit and the Leadership and Design unit at the Ontario Provincial Police Academy.

The Ontario Provincial Police were in the midst of responding to a scathing 2012 Ontario Ombudsman report about stress injuries and suicides in its ranks, when Shipley crossed paths with Andersen. “This (type of training) will really move police training forward,” he says, adding police leadership needs to be open to research-based relationships where research guides policy and training curriculum.

He sees Andersen’s work as offering tangible ways to keep officers healthy, protect the public and bring officers back to work sooner after a traumatic incident.

Typically, OPP officers take 12 weeks of courses at the Ontario Police College and eight more weeks of enhanced front-line operational training. Officers with the Toronto Police Service also take the 12-week course at the police college, and then receive an additional 12 weeks of orientation and training.

This stands in stark contrast to Finland, where, with Andersen’s input, the nation’s Police University College has developed a three-year university level program for its trainees. “We need more police training,” Andersen says, adding it’s shocking that it takes longer to receive a hairstylist’s license in Ontario than it takes to become an officer.

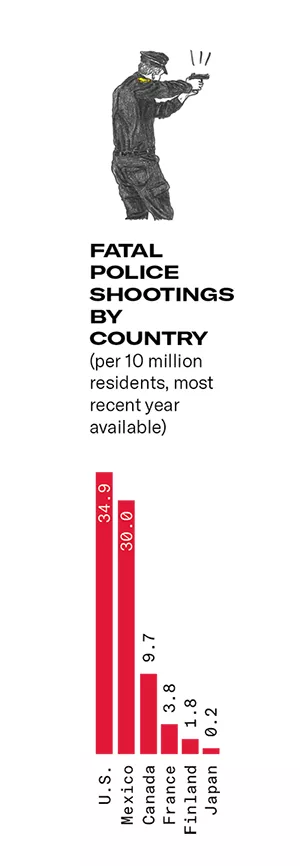

She points out that Canada and Finland have similar rates of crime and drug use. And, like Canadian officers, Finnish police carry guns. However, on average, Canada has five times as many police-related shootings – 9.7 per 10 million people compared to Finland’s 1.8.

Just this fall, Ontario Ombudsman Paul Dubé blasted the province’s police training model, which he says emphasizes weapons over de-escalation. It’s an echo of the same criticism he levelled back in 2016 when he released his report, A Matter of Life and Death, which was critical of inadequate police training.

In Ontario, recruits are taught about weapons, tactics and the concept of de-escalation. They receive some scenario training and emotional coping techniques, but no one teaches them how to control their internal response. Yet these internal body processes are what affect behaviour, actions and emotions and, ultimately, the safety of the people officers interact with.

Finland’s approach demonstrates that developing self-awareness and modifying the body’s response to stress can be learned. Andersen says with training and continued practice, the modified response becomes automatic, much like driving does with time and practice. The training, she continues, needs to be applied at the recruitment stage and throughout the entire career of a police officer.

Teaching trainees how to modulate their response and “control the cascade of stress chemicals” helps them shoot less often and more accurately, Andersen says. It also helps them cope with job-related stress at the end of their shifts. That ongoing tension wears on people and remains invisible to others unless the officer reports it.

Andersen took up this line of research during her graduate and post-doctoral studies when she built a program of research examining the effects of stress responses on mental health and occupational performance. At the time, few people were drawing evidence-based links between trauma and physical ailments.

“It’s not just all in your head,” she says. “It really is physical.”

After moving to Canada, she chose to focus on resilience in the face of trauma. In 2013, she connected with police trainers in Finland where officers are among the most respected public servants.

At a time when the public conversation about police restructuring is gaining momentum, Andersen wants to see the public continue to push for changes in how police are trained, saying the resistance to change needs to be addressed.

This story first appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of University of Toronto Magazine