What’s in a road name? UTM history grad explores Mississauga’s colonial connections

The recent rise of anti-racism movements across the globe have prompted collective reflection on how we label our public landscapes. The names of buildings, sites, statues, streets and more are being freshly scrutinized, and in some cases renamed, as we come to terms with our settler history and strive for greater social justice.

To understand this issue in the local context, we can turn to timely new research completed by U of T Mississauga Historical Studies graduate Omar El Sharkawy. For his one-year internship course with Heritage Mississauga, El Sharkawy studied the toponymy of a few main roads in urban Mississauga. His investigations resulted in Colonial Connections and Naming Mississauga, a five-part article series on the decision-making behind some of the city’s high-profile street names, and the ideological dynamics that were at play.

“Road names subtly reflect the power relationships and politics in a given time and place. We tend to look at these names with a modern lens and cast judgment,” says El Sharkawy, whose series has been publishing weekly as of July 7 in Modern Mississauga’s online magazine, and will also live on the Heritage Mississauga website.

“I tried to contextualize the names by illuminating the history surrounding how they were chosen. Understanding this context allows us to be more informed about how we address issues of racism and marginalization.”

Mid-20th century Mississauga was characterized by a new wave of British-influenced Anglo-Canadian nationalism. Drawing on a mix of primary and secondary source materials, El Sharkawy explains how, while postwar Canadian national consciousness began shedding its Britishness and redefining its identity, Mississauga strengthened its attachment to the “motherland” through municipal decisions that imprinted British names onto the cityscape.

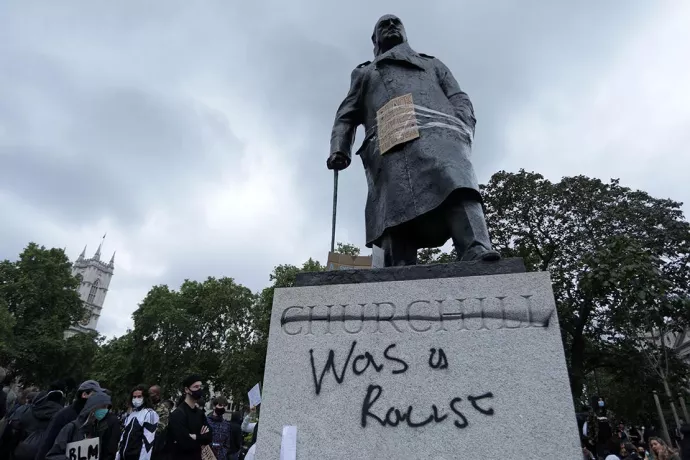

One example El Sharkawy shares is Winston Churchill Boulevard, the major north-south roadway commemorating the accomplished British statesmen and wartime leader. The road was renamed from Town Line in 1965, the year Churchill died, at the suggestion of Ron Searle, an English-born Mississauga councillor—and mayor from 1976-78—who was supported by his fellow conservative political peers. Yet this was also the year Canada grew more into its own distinct nation by adopting the new maple leaf flag.

“Searle and his peers had a specific interpretation and perspective regarding Churchill’s legacy, and they were certainly not a minority around the world given the enduring Churchillian legacy of the Second World War. Concurrently, they did not speak for all of Mississauga’s citizens, nor did they entirely represent the most popular nationalism of postwar Canada," Sharkaway writes.

Today, Winston Churchill Boulevard is the focus of a renaming movement because of Churchill’s disparaging comments about some BIPOC groups. So is another road El Sharkawy covers in his research: Dundas Street, the major east-west artery connecting Toronto to Mississauga and other southwest Ontario cities. John Graves Simcoe, the British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 to 1796, named the street after Henry Dundas, the 1790s British Home Secretary and abolitionist obstructionist.

As El Sharkawy explains, naming the street Dundas was part of Simcoe’s “British settler project…that enforced a colonial ideology via the developmental and toponymic restructurings of the landscape.” Earlier this month, Toronto City Council voted to rename the street to promote the inclusion of marginalized communities.

“Omar’s research couldn’t be more timely. He did an amazing job of putting historical street naming in Mississauga into the context of the times,” says research supervisor Matthew Wilkinson (BA 2006), a historian with Heritage Mississauga. “It’s a dicey issue when we begin to reshape the landscape according to modern ideology. Omar’s work says, let’s not draw conclusions, but have an open conversation about what these names mean.”