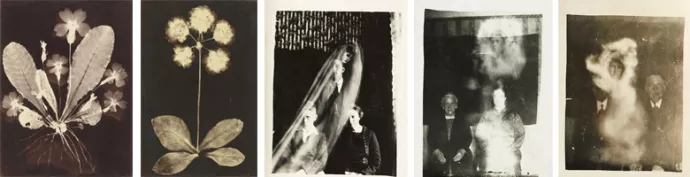

Botanical photogram (1860s). Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

William Hope, Woman with two boys and a female spirit (1920). Courtesy of the National Media Museum.

William Hope, Two women with a female spirit (1920). Courtesy of the National Media Museum.

William Hope, Two men with a female spirit (1920). Courtesy of the Collection of National Media Museum.

How to Address Professors

Every educational institution has its own culture and its own expectations of the level of formality between students and professors. If you’re in a joint program with Sheridan, you may find students and instructors are on a first name basis and the conversations are pretty casual. At UTM, professors expect you to call them “Professor X” or “Dr. X” unless you’re invited to call them by their first name. One system isn’t better than the other; it’s just two different ways of doing things. At UTM it’s considered a sign of respect to address your professors formally and cultivating a culture of mutual respect is in everybody’s best interest.

How to Email Professors

Likewise, a higher level of formality is necessary when you are writing emails to professors than when you are writing to your friends. Suppose you needed to contact your Program Director about an important matter. You could begin with “Dear,” “Good morning/afternoon,” or “Hello Professor Kaplan,” but not “Hey Louis.” Emails should be written in full sentences and paragraphs with proper spelling and grammar. The tone should be formal and respectful.

Be sure to give the reader the information he or she needs to properly respond to your question. Your professors and T.A.s have many students in multiple classes. It is important that you tell them which class you are in, which tutorial session, which T.A., to which assignment you are referring, etc. Precision is as important in email writing as it is in essay writing.

Attendance

Attending lectures, tutorials and screenings (as well as tests and exams) is mandatory. You must attend every class unless you are unable to do so because of illness or accident. Please refer to the Absence Policy for instructions on how to proceed if you miss a term test, exam or assignment due to illness or accident.

Punctuality

Just as important as attending is arriving on time as well as staying for the entire class. Plan to arrive five minutes before the start of class. Late is late, whether it's two minutes or 25 minutes; it’s disruptive and disrespectful. You only have a few hours a week to meet as a class and that time is important — it’s the core of your university education.

Handing in Assignments on Time

It’s important to hand in assignments on time. It’s a good idea to start out on the right foot handing everything in on time from the beginning of first year. Once you start handing things in late, it’s a slippery slope. Even though your syllabi will indicate how much your grade will be reduced per day that it’s late, it’s not meant to be a sliding scale or a negotiation. It comes down to being responsible and preparing for life after university. Remember that no matter what you end up doing after university, you will be expected to meet deadlines. Handing your assignments in on time shows that you can manage your time. If you consistently feel like your course load is more than you can handle, consider scheduling a meeting with the Undergraduate Counsellor to plan out a course timetable for the next term that allows you to meet your educational goals and get the most out of your time here.

Picking Up Assignments

You are also expected to pick up graded assignments. A great deal of time and energy is put into evaluating your work. If you don't pick it up, you can't learn from the feedback your instructors have given you.

Course Load

In recent years, it has become a concern that more and more students are overloading on courses beyond the standard five courses per term. Faculty have found this to be counterproductive to student success. Spreading oneself too thinly detracts from the quality of your learning experience. We strongly discourage you from overloading your timetable. Similarly, we strongly discourage the practice of scheduling courses such that there is any timetable conflict, no matter how short the overlap. If you come across a potential scheduling conflict that you cannot resolve, please contact the Undergraduate Counsellor.

Plagiarism

It is never a good idea to plagiarize (in fact, it is completely unacceptable). Aside from the fact that you won't learn anything, plagiarism will not save you time in the long run. Your professors and T.A.s grade hundreds of papers per year: plagiarism is immediately obvious to them. And we do process every case. Sanctions range from zero on the assignment to suspension from the University. If the assignment is worth more than 10 per cent, your professor and the department have no control over determining how your case is handled. The case will go straight to the Office of the Dean for resolution, which may mean delayed marks, delayed graduation and other bad outcomes. Just don’t do it; it’s not worth your time. If you can’t get an assignment in on time, speak to your professor. Plagiarism devalues all the hard work a student has done up until that point.

The professors in our department use Ouriginal for submission of assignments. It is an excellent tool for preventing and deterring academic offences.

You can find more information on plagiarism in the University of Toronto’s Code of Behaviour on Academic Matters.

If you are unsure what constitutes plagiarism, you must make yourself aware by researching U of T's policies, communicating with your professors, and seeking help at the Robert Gillespie Academic Skills Centre. Margaret Proctor’s “How not to plagiarize” is also a very helpful resource.

Reading

If you’re finding that some of the readings in university are long and difficult, you don’t need to feel alone. Most people feel this way. It’s normal to have to read sentences more than once in order to understand them, especially if you are required to write about the text. You’ll be grappling with challenging ideas here and it’s not supposed to be effortless. You may have learned to read 15 years ago or more, but your reading skills will continue to develop in new ways over your university career. The more you struggle with texts, the stronger your critical faculties will become.

Aside from that, you do need to do the readings for every class and come to class prepared. Having another assignment due is not a valid excuse; the readings were an assignment too.

Writing

Writing for university courses can be overwhelming at first. Think about what you might want to do ahead of time and consider booking an appointment during your professor’s office hours. Discussing your intentions with your professor can be a huge help. He or she can suggest questions you might think about, point out key sources you should look at or steer you away from a project that is too large and unwieldy.

Reference Letters

When you’ve finally made it through the program and if you decide you might like to continue on to graduate school, professional school or a post-graduate college program, you may find that you need letters of reference for admission and scholarship applications. There is no need to feel bad about asking your professors to write letters for you — they got to where they are now by asking their professors to write letters for them. However, letters do take time, and there is an etiquette around asking for them. Adam Chapman’s article “How to ask for a reference letter” in University Affairs gives excellent advice. Although the article is aimed at PhD students, many of the factors are the same for undergraduates.