Claudiu Gradinaru on Dancing Proteins, Super Lasers, and the Future of Biophysics in Canada

Guided by an innate curiosity and a firm belief in the power of scientific collaboration, Claudiu Gradinaru is a strong voice in Canada's growing biophysics community — and he believes it has an important role to play.

Dr. Gradinaru is a professor of Biophysics in UTM's Department of Chemical & Physical Sciences and the incoming president of the the Biophysical Society of Canada. A long-time history buff with a hands-on teaching approach and a passion for Pink Floyd, Gradinaru is co-recipient of this year's Desmond Morton Annual Research Award. With the Research Excellence Lecture just around the corner, we sat down with him to learn more.

Can you speak about your research area?

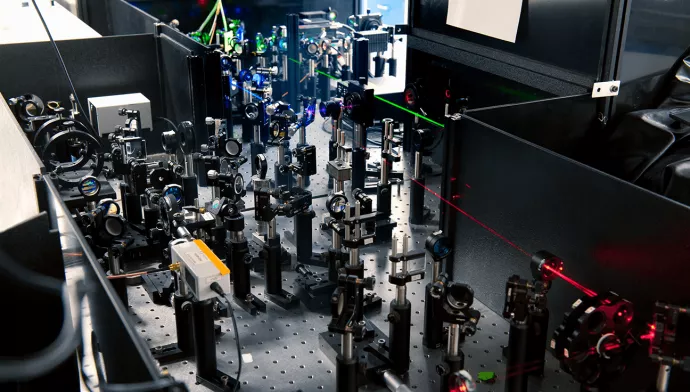

I’m a biophysicist, so I’m at the intersection of two major areas of scientific research: biology and physics. In particular, I’m interested in proteins, the building blocks of life, which are involved in most biological functions. They are at the root of understanding disease, and of developing new therapeutical drugs. I use lasers, cutting edge detectors, and advanced data analysis routines to decode this molecular choreography of proteins by looking at them one at a time.

We’re dealing with complex systems, and disease is just an outlier — so if you just take an average, you wouldn’t see that your system is misfunctioning. You have to measure the entire distribution of behaviours and only then can you capture any anomalies. It’s pretty tricky to measure one molecule at a time. In order to see the signal in the noise, you need to come up with all kinds of tricks, from designing the experiments to analyzing the data, to really make sure that you’re looking at a single molecule of interest. So that’s what I do: I use light to decode the nanoscopic dance of proteins inside our bodies.

What led you to your field and to this area in particular?

Growing up, I didn’t have a bias toward science. I also loved history, geography, and philosophy, and I was always curious. As a kid, my parents were exasperated because I was always breaking my toys. Toys wouldn’t last more than a couple of days, because of my innate curiosity to see what was inside, what made them work. I owe quite a bit to my grandmother, too; she taught me to read at very early age. People in her village would look at me like I was an alien, reading the newspaper at four years old and talking about foreign affairs. [laughs] I read many books — and as it happens with many, there are teachers who come your way and inspire you.

In middle school I was inspired by a math teacher, and then in high school I was inspired by a physics teacher. They both really channeled my curiosity. I think it matters who inspires you, and how lucky you are to encounter people either in your family or the school system to help you to channel your enthusiasm so you can discover yourself.

Where were you raised?

I’m fortunate and unfortunate at the same time. I grew up in Romania during the communist times. But the caveat is that the system changed — the Revolution happened when I was 17, just the right time to have both some formative years and experience of that system to understand and appreciate freedom and democracy. But at the same time, I was young enough that my personality wasn’t fully molded into that depressing model.

My college and graduate studies took place in the democratic system of the 1990s, so I was fortunate in that respect. The change came at the right time for my generation.

Can you share a bit about the Gradinaru Lab and your work with students? What’s the team dynamic like?

My management philosophy is to lead from the middle. I don’t want to just tell people to come back to me when they have results. When I recruit new people, they ask if the prof is hands on or off and my team members will always say hands on. I still don’t know if I should take that as a plus or a minus… [laughs]

But I strongly believe that I should show commitment and involvement. I’m here every day, and I always go to my lab to check how things are going and see if my team needs my input. I have lunch in the kitchen lounge on the fifth floor with my team and other trainees from neighbouring labs because I believe in the sense of community, that we really are in this together. They are the ones doing the science and I should not be detached from them, from their problems, their thoughts.

Having said that, I enjoy it most when they show initiative. It’s a fine balance between being too involved and letting them flourish. I understand the role of independent, critical thinking, of hearing their own ideas. And they get my feedback regularly. We have weekly one-on-one meetings, and in our team lab meetings, we set ground rules and take an approach where we are honest, and everyone knows where they stand. It’s part of being on a team — and they have to talk to and teach each other.

Science is very social. If we cannot share the information, we’re lost. The COVID pandemic showed us that.

What are you currently working on?

I like to build optical instruments, and because what I do relies on advanced instrumentation, I can’t just let it become obsolete. Recently we got a Supercontinuum Laser, an amazing piece of equipment that emits short pulses of white light, with all colours coming out of a single fibre. I have control over what colours to use for a particular experiment, and their timing sequence. It’s amazing stuff that, when I started out my lab 17 years ago, I could only dream of. This continuous technical development is part of what I do.

But most of my time is dedicated to studying biological systems. There are two classes of proteins that I’m focused on. One of them is intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), highly dynamic, “shapeshifter” proteins that play important regulatory roles. I do single-molecule experiments on these weird molecules that exhibit ‘force without form’, to quote a famous Canadian band. As IDPs don’t have a stable structure, how can we rationalize their interactions with other biological molecules? Right now, in collaboration with Dr. Julie Forman Kay from Sick Kids, we seek to figure out what physical principles are at the basis of forming fuzzy, dynamic IDP complexes.

The other system is G Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCR), the largest family of membrane proteins and the major target of pharmaceutical drugs. I collaborate with Scott Prosser and others to figure out how binding of ligands modulates the structures and the dynamics of these proteins and what are consequences for cellular signalling and for designing more potent and specific drugs.

Your lab collaborates with several groups – both within the U of T community and with industry partners. How important are these collaborations?

A lot of people claim to be interdisciplinary, but I really am — even the very name “biophysics” has an interdisciplinary ring to it. I really believe that you can’t know it all, you can’t specialize in everything yourself. Yes, I use physics to look at biological systems, but I rely on chemists, biochemists, and biologists to complement my expertise.

If you are true to being interdisciplinary, you must collaborate — and you must really collaborate, not just having some samples shipped, but having regular meetings to discuss results and form new ideas. I’m fortunate to work at a top research university with many experts in many different fields. If you say you don’t have anybody to collaborate with, it means you didn’t make an effort.

How does being based at UTM help support you in your work?

Here at UTM, I’m especially fortunate. I’m in the department of Chemical and Physical Sciences, an interdisciplinary department par excellence. UTM physicists are mostly in biophysics and the chemists are mostly in the bio/organic/medicinal subfields. As such, my lab is on a floor and in a building where I can easily interact with chemists and biologists, which is ideal for my research.

Environment, environment, environment. It’s key.

Is there anything we haven’t asked that you feel would be of interest to our readers?

Physicists are often seen as aloof or socially challenged, portrayed as such in popular culture, in shows like The Big Bang Theory. But I believe that physicists are a fearless species of scientists, sometimes coming across as arrogant, who are not afraid to embrace any challenge. They try to understand the mysteries of everything in the material world, from atoms to the entire universe.

Living systems is a relatively recent addition as a subject of study for physicists. I can say I was a little surprised coming to North America to see that biophysics was primarily integrated in medical sciences and biochemistry, not in physics departments. However, I think we’ve made a lot of progress over the last two decades. As incoming president of the Biophysical Society of Canada, I can tell that the biophysics community in Canada is growing. It’s good news because I believe that our community has an important role to play in discoveries in life sciences. We care a lot about numbers and mechanisms, and you need to know how stuff works if you want to design it yourself and control it.

I’m also glad to see that students at all levels are no longer afraid to embrace this interdisciplinarity, because we grew up in silos. I’m a chemist. I’m a physicist. I’m a biologist – I think those times are over. And they have to be, for us to face the challenges of the future.

Listen to Professor Gradinaru and co-recipient Professor Yuhong He (Department of Geography, Geomatics and Environment) discuss their research at the Desmond Morton Research Excellence Lecture. This virtual event will take place Thursday, January 26, 2023, from 1:00-2:00 PM via Zoom. Visit the event webpage to learn more and register.

Each year, the Desmond Morton Research Excellence Award recognizes outstanding career achievement in research and scholarly activity by faculty members of the University of Toronto Mississauga.

If you would like to nominate an exceptional researcher in the sciences for this award, the call is now open for submissions. See the Research Excellence Award webpage for more information.