UTM students get field work experience at home with portable sensors

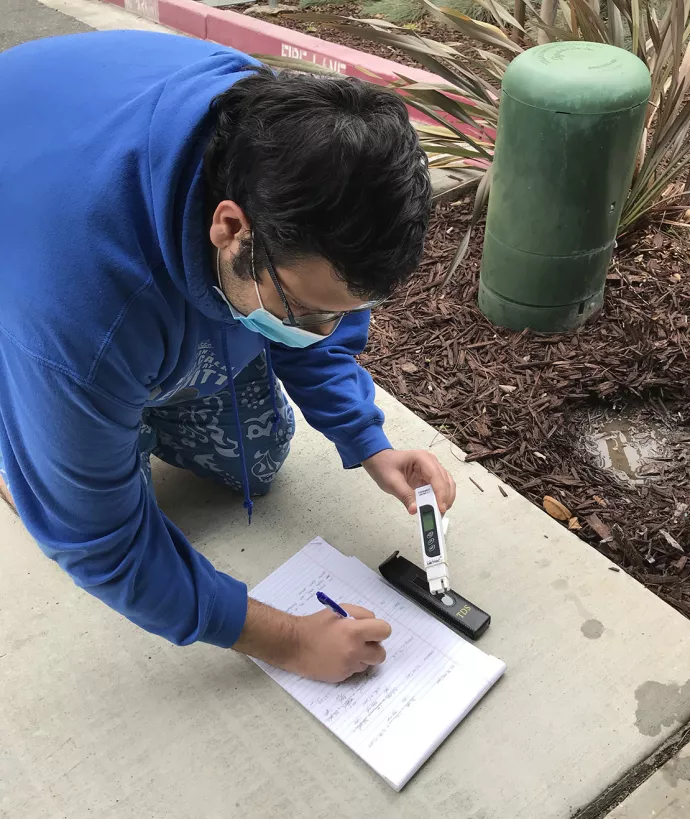

Late last fall, Jamsheed Mistry spent several evenings in a park near his home in San Jose, California, measuring the salinity of puddles. Armed with a hand-held water quality meter, he was investigating how the surrounding environment influences salt levels in urban run-off. The results went into a database shared with his classmates in an environmental science course at U of T Mississauga, so he took extra care collecting and recording them.

That’s what made the whole exercise so interesting, says Associate Professor Monika Havelka, who taught the Experimental Design in Environmental Science course. “We had students not just in the U.S. and provinces outside Ontario, but also in Asia and the Caribbean, which added a new and interesting dimension to the research.”

Havelka, like many faculty members across the university, redesigned the field-based elements of her course in response to pandemic restrictions. To ensure that crucial real-world learning opportunities were not lost with the shift to remote education, the Office of the Dean at U of T Mississauga offered Experiential Learning Development Grants to offset costs such as software licenses, research assistance and – in Havelka’s case – equipment purchases. The Department of Geography, Geomatics and Environment also contributed funding.

“In thinking about how we could deliver this course remotely, I knew we had to choose equipment that would be simple for students to use on their own,” she says. “Normally we’re all together so I can help answer questions or advise them on the best techniques. But this time students went into their neighbourhoods and had to figure things out on their own.”

Mistry and his classmates had no trouble using the water quality meters, and there was a high level of engagement across the class, according to Havelka. “They demonstrated a sense of individual responsibility and accountability beyond what I sometimes see during in-person field work.”

Assistant Professor Trevor Porter, who also restructured the experiential learning component of his course, Field Methods in Physical Geography, observed the same spirit of self-reliance in his students. “To a large extent, their learning was self-guided in their own communities,” he says. “They showed professionalism and maturity that will take them a long way when they graduate.”

Porter used the experiential learning grant to buy urban air pollution sensors for every student. The devices use laser particle counters to determine the amount of dust, smoke and other organic and inorganic particles in the air. He created troubleshooting guides – including videos – for students, but says there were no issues with the equipment. “The students set up the sensors in their backyards or wherever they could, then devised individual research questions. For example, does particulate matter vary between day and night?”

Before the pandemic, Porter took students in this course to a field camp in the Haliburton Forest before classes officially began in the fall. “It’s a wonderful natural classroom for hands-on learning where students can study anything from tree growth and soil quality to aquatic systems.”

Shifting to research in the urban environment fostered the same field skills while adding new meaning to the results, he says. “Many of the students chose to explore questions that connected to things they care about personally. One student loved shopping at outlet malls, so she explored whether all the car traffic and idling created poorer air quality in these settings compared to adjacent areas.”

Havelka noticed the same enthusiasm for gaining a deeper understanding of the urban environment in her students. “I had so many say that they looked at their familiar surroundings with fresh eyes after collecting data there,” she says. “And that’s exactly what we want to do in environmental science – have students connect to the fact that the issues we’re concerned about are all around them. Whether it’s water quality or air pollution, these are not abstract things.”

Beyond the specifics of the research projects, both Havelka and Porter worried that the camaraderie of field work among peers might be lost in their remote courses. “When you gather around the campfire at the end of the day up north, it’s easy to feel a sense of belonging to a research community,” says Porter. “We had to simulate that as best as we could through virtual collaboration and peer review, and I think it worked well.”

In Havelka’s course, Mistry says he forged strong bonds with his classmates online. “We often chatted about our data, and generally relied on each other for support and guidance. It was a really interactive experience with Professor Havelka, too. I went to her virtual office hours more than I ever would have on campus.”

The success of the students’ independent data collection and the excitement it sparked in them has prompted Havelka to consider keeping this approach – even after the return to in-person learning. “I may adopt a hybrid model that retains some of these individual exercises.”

As for Mistry, he says the course reinforced his passion for field work and confirmed his decision to begin graduate studies in environmental studies this fall. “When I first read the syllabus, I honestly wasn’t sure it would work. But it turned out to be one of the best courses I’ve ever taken.”