UTM student finds microplastics in water downstream from manufacturing companies

U of T Mississauga student Nicholas Tsui and a team of researchers have confirmed that plastic pellets used by local manufacturers are in local waterways. The team is now working with the plastics industry in an effort to curb the number of microplastics being released into the environment.

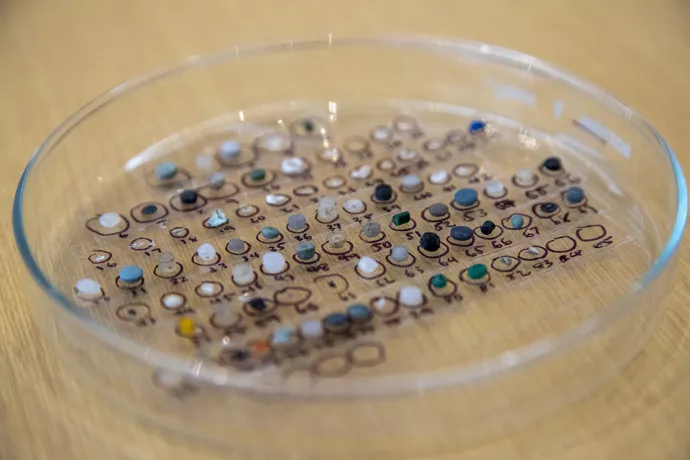

Tsui, a student in UTM’s Master of Science in Sustainability Management program, spent two months dipping a fine mesh net into Mimico Creek at Tom Riley Park in Toronto, downstream from plastic manufacturing companies in Brampton and Toronto, to collect samples of tiny plastic pellets called nurdles.

“We can demonstrate that microplastics are in the environment,” Tsui says, explaining the team found “quite a few pellets.” There are about six pieces of plastic floating on top of every single cubic metre of water, Tsui says.

And that’s moving water, he stresses. “Imagine the amount of water that flows through the creek in a day.”

Plastic pellets, which are shipped by truck, rail and sea, are the building blocks of plastic production. They are melted down and injected into molds or blown into shapes, Tsui explains.

Ontario is home to half of Canada’s plastic manufacturing, where the pellets are shipped by train and truck. The process of transferring the tiny pieces of plastic is “notorious for spills,” Tsui says. “When transferring from rail cart to company, there is always spillage.”

Those lost pellets sit in the gravel and, when it rains, run into storm drains and subsequently wash into creeks and lakes. Tsui refers to the storm drains as “a sinkhole for microplastics.”

Some seabirds and fish confuse the plastic pellets for food and eat them, causing some to choke and some to die of starvation, Tsui says. Whether the chemicals found in the plastics accumulate in birds remains to be seen, he continues.

Armed with proof that plastics are being released into the local environment, the researchers contacted the 18 identified local manufacturers along the Mimico watershed. Only one responded, Tsui says. He is careful not to discount the other companies, explaining some already have better practices in place and at least one is under a stringent, audited responsible care program, but “quite a few, ignored us, sadly,” he says.

Along with environmental considerations, there are economic incentives for manufacturers to reduce the release of microplastics. Tsui explains the loss of microplastics is a loss in profit (product is being lost), a litigation risk and a reputational risk for companies.

There is one voluntary industry-based solution endorsed by the Canadian Plastics Industry Association called Operation Clean Sweep, which is a set of management best practices to help reduce pellet loss, with a goal of zero loss. Examples of best practices include placing a basin under the rail cart valve to catch any spills or using stormwater filters. Behavioural change, however, is the hard part, Tsui says.

With increased awareness and attention to the issue, the willingness to change may be growing. The research Tsui was able to undertake, for example, was what he describes as an unconventional partnership, noting it was a collaboration that included not only the Ontario government, but also the Canadian Plastics Industry Association.

With environmental concerns and microplastics a top issue, Tsui is looking for more industry buy-in, government action, and collaboration to reduce the release of microplastics.

The research team is still reaching out to companies to discuss opportunities to mitigate risk and reduce the release of microplastics into the environment.

“I think it’s a really good time right now because of the current trend of sustainability and demand for corporate responsibility,” Tsui says.