Selling the ideal body: New UTM course traces history of health and fitness in advertising

From 20th century strongmen to Gwyneth Paltrow’s infamous jade egg, a new course at U of T Mississauga explores how self-styled health-and-wellness experts influence and profit from the pursuit of the perfect body.

Special topic course "Visuality and North American Fitness Culture" uses advertising to explore the ever-changing—and sometimes repeating—health and fitness fads of the past century.

“Visual advertising and commercial cultures change over time, and so does what they might tell us about what the body should look like,” says sessional instructor and historian Dan Guadagnolo, who teaches the third-year special topics course offered through UTM’s Department of Visual Studies visual culture and communication program.

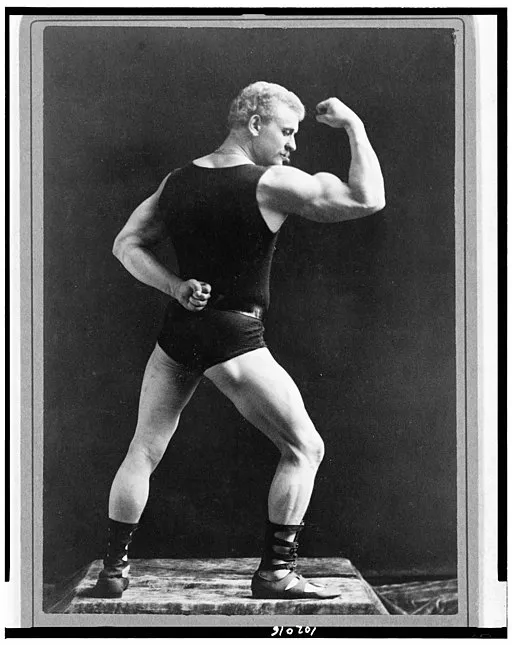

Library of Congress, Public Domain

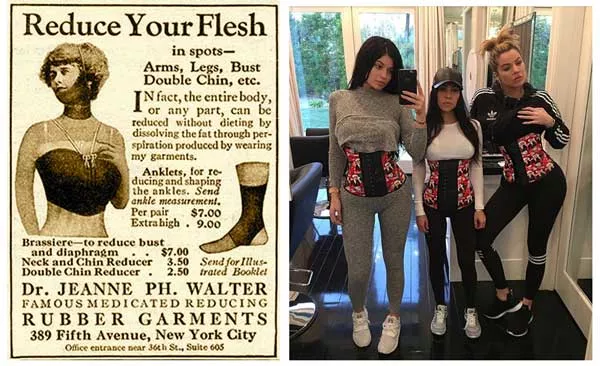

“Fitness fads are one way to explore how commercial culture has created and preyed upon our insecurities about our bodies, and how it has shaped what society thinks of as the ideal body,” he says. “Looking at how these tools have developed as visual rhetoric in the past century can help us think critically about what we’re being sold today.”

Guadagnolo surveys historical advertising campaigns that reveal popular ideas of gender, identity, class culture and ethnicity. One lecture covers the influence of Eugen Sandow, a popular Prussian-born weightlifter often referred to as the ‘father of modern bodybuilding.’ At the height of his popularity in the early 20th century, Sandow lent his name to health tonics, mints, and even a dried beef product snapped up by an audience who aspired to look like him.

“Sandow was imagined as the perfect man—civilized, respectable and powerful,” Guadagnolo says. “These figures served a powerful role in culture to indicate what was valued or important as the idealized body.”

“Today, on Instagram, this is the primary way fitness influencers sink their teeth into unwitting consumers who feel the need to escape their body type,” he continues. “Their work is achieving the best possible body. They offer discounts to supplements, access to personal training plans and all manner of services that might help realize this body, but they functionally trade in an economy of shame.”

“But the ideal body is a social fiction,” he continues. “There are no absolute scientific truths, although merchandisers and marketers want you to believe that what they are saying is scientifically true.”

Marketing of health and fitness fads is focused on ideas of perfection and sales and often faux science. Some were even deadly, such as the “radium mania” that swept North America in the early part of the 20th century. Radium was viewed as an endless source of energy, and the market introduced radium-infused products, including radioactive water, Guadagnolo says. The original energy drink made headlines when it was linked to the death of an American socialite who consumed the radium-infused water for three years believing it would give him superhuman strength.

For every historic fad, there’s a modern-day counterpart. “In the 1890s, people were just beginning to use electricity and having new ideas about how it might be used to restore energy to the human body,” Guadagnolo says. A century later, the health industry is still marketing electronic devices like the Abtronic, an early-2000s electronic belt that promised to develop abdominal muscles through electric stimulation.

Students often bring examples of modern-day fads, including crystal therapy, Soylent meal replacement, chin straps, waist trainers and the jade egg marketed by Gwyneth Paltrow’s GOOP website.

“I want students to recognize the visual tropes and value that is attached to certain bodies, and to be able to deconstruct and interrogate those outlandish claims about how to be well or how to be healthy,” he says. “It’s grossly unethical and they should have the power to figure out when they’re being taken advantage of.”