Confronting the Past: Grappling with Germany's legacy

As a country, Germany has confronted its past. But for families, angst about the war persists. My father demanded an explanation from his mother about what she did during the Holocaust. Like many of his generation, he never got it.

Last year, on a grey January evening, a taxi dropped me off at Pauly Saal, an impossibly hip restaurant in Berlin. It is housed inside a former Jewish girls’ school. The architecture has been painstakingly preserved, from the tiled floors and cement walls to the institutionally prescribed bathrooms, updated only by new stall doors and fancy towelettes. The restaurant is in the former gymnasium: a simple square room that has been transformed with green velvet banquettes, cutesy stuffed foxes, and an enormous red rocket above the open kitchen. The food is a modern take on traditional German dishes: hearty, delicious and expensive.

I walked slowly past the placards explaining the history of the building. It was designed in the late 19th century by a Jewish architect who met his end in the Theresienstadt ghetto. The Nazis closed the Jewish girls’ school in 1933, and the vast majority of the students met their ends in death camps in Poland. In 1996 it was finally returned to the Jewish Community of Berlin by the Claims Conference. The German Jewish Council rents it out to entrepreneurs. And so I find myself eating here.

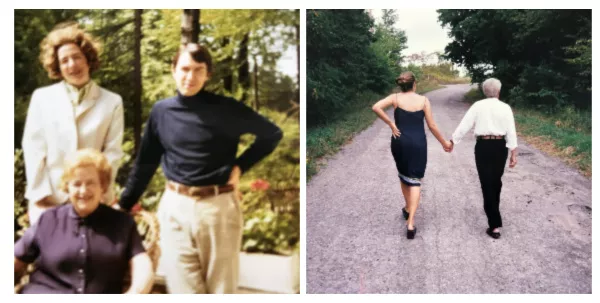

The existence of such a chic restaurant inside a former Jewish girls’ school made my father’s stomach turn. Born in 1935, he grew up in West Germany and was plagued his entire life with shame and horror at the crimes committed by his parents’ generation. He left West Germany for North America at the age of 28 and only ever returned for brief family visits. Like many young Germans in the aftermath of the Second World War, he felt suffocated by the guilt of a previous generation who never took responsibility for their actions during the Nazi period, and who refused to even discuss what had happened. Confronted with his own mother’s silence (his father had died during the war), my father faced a tormenting moral choice: be complicit in his mother’s silence or speak out against her.

My father never stopped loving his mother. But he also rejected her – and his sister (who took his mother’s side). He left the country and excluded both from his wedding. Some 40 years later, my aunt and grandmother called my father’s decision a “Trennungstrauma” (separation trauma), and felt bitter that in rejecting the country of his birth he had also rejected them; he seemed to hold them personally responsible for Germany’s crimes.

I do not imagine my family to be so very different from other German families coping with the burden of crimes committed in their names, often by their relatives. How do successive generations cope with the past under these conditions, in which those who committed the crime – a whole generation – refused to take responsibility? Almost every German I know has questions and stories about a relative’s mysterious actions during the Nazi period. Yet the moral indignation expressed by my father and others of his generation was certainly not the norm; the vast majority preferred to sweep the past under the rug, just as their parents had.

Ironically, as a nation, Germany has done a very good job of confronting its past. Who else builds a memorial to its own crimes the size of two football fields in the centre of its capital? Where else do you have an almost daily discussion in the media of the atrocities of the past? For this, I credit a very loud few, like my father, who wanted answers. But many Germans greeted the process with resentment; they didn’t want an investigation into their parents’ past.

Admission of guilt on the official, national level is very different from a personal admission of guilt. My father demanded an explanation from his mother, even after Germany had begun to acknowledge its crimes. Why did she insist that “it wasn’t all bad back then”? Why didn’t she object to the bust of Hitler in her friend’s living room? Ultimately, I think, he felt her silence, her willful ignorance, her defensiveness were acts of complicity.

This deduction was central to the lessons he taught me, and is now very much part of what I teach students about the slippery slope of indifference, apathy and collaboration. An official, national admission of guilt is not enough. When individuals refuse to accept responsibility for crimes that were committed with their tacit consent, the crimes can easily be repressed, forgotten and, ultimately, repeated. The motto for International Holocaust Remembrance Day is “never forget.” For my father, and for me, this must be more than a slogan remembered on one day a year. It must be a collective reckoning not only by governments but by the individuals who supported, allowed or simply turned away from the brutality and tyranny of oppression and mass murder. This personal reckoning has not taken place in Germany. The divide between the official government position – welcoming more than 1.5 million refugees since 2016 – and the growing populace of resentful right-wing nationalists, attest to a great chasm between official German atonement for Nazi crimes, and personal unwillingness to recognize that individual Germans made those crimes possible.

My father, who died last July, was uneasy when I told him about my dinner at Pauly Saal. For Germans of my generation living in Berlin, the discomfort also lingers: recounting my dinner to a friend, she worried that the Holocaust would become nothing but bittersweet folklore. At the same time, she recognized that more people might learn something by eating at this fancy restaurant than if it had been turned into yet another museum. This process of confronting the past is complicated and uncomfortable. But it must certainly continue.

Rebecca Wittmann is an associate professor of history at the University of Toronto and chair of the department of historical studies at U of T Mississauga. Her research focuses on the Holocaust and postwar Germany, trials of Nazi perpetrators and terrorists, German legal history and Holocaust memory. This article originally appeared in University of Toronto Magazine.