Peering inside the teeth of a 289 Million-Year-Old plant-eater

https://youtu.be/wsSFLF0_gcI

https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9168

Land-based communities looked very different during the early Permian period, about 289 million years ago. Instead of hosting an abundance of plant-eaters supporting a smaller number of carnivores like today, the early Permian featured many carnivores, big and small, while only a few species experimented with eating plants. Of these intrepid herbivores, small reptiles, called bolosaurids, were apparently ahead of their times. A new study published in PeerJ has figured out just how unique these herbivores were.

Despite their small, iguana sized bodies, bolosaurid reptiles were some of the first herbivores who used their teeth to grind plant materials between the upper and lower jaws. This was possible because they evolved large, complex teeth. But bringing the upper and lower teeth together to grind food required some other important evolutionary changes that have remained a mystery. Like nearly all other reptiles, bolosaurids apparently replaced their teeth throughout their lives, but their fossils almost never show the telltale toothless gaps that are so common in other reptiles.

The mystery of how bolosaurids maintained full rows of grinding teeth despite continually replacing them was solved by a research team led by undergraduate student Adam Snyder and Professor Robert Reisz at the University of Toronto Mississauga. Using state-of-the-art CT scanning techniques and by making microscope thin sections of some bolosaurid fossils, the researchers were able to peer inside the teeth and jaws of these ancient herbivores.

Adam Snyder was very excited by the opportunity to combine CT scanning of fossils using both regular X-ray and neutron scanning technologies, with high quality tissue level histology. “Adam worked very hard learning all these techniques, and this approach yielded some startling discoveries”, said Reisz.

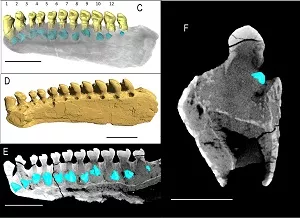

Adam found that the teeth of bolosaurids from North America, Europe, and China turned out to be very deeply set in the jaws, the roots being larger than the crowns, a condition seen in modern crocodiles and mammals. “There was a lot of space inside of the functional teeth where the replacement teeth could grow to an advanced stage, so that they could come up quickly when the older ones were finally shed” said Snyder.

Most surprisingly, CT data showed that one of the complete lower jaws of a bolosaurid had replacement teeth growing under each adult tooth, suggesting that new teeth were growing inside of the jaws for a long time and in a synchronized way. Instead of replacing even- and odd-numbered teeth in different waves, like in most other reptiles, bolosaurids replaced their teeth one at a time, and very quickly. This allowed them to maintain as many teeth in the mouth as possible at any given time. “When taken all together, these dental features show just how well adapted bolosaurids were for grinding down their tough food” said research supervisor Reisz.

The research team also included former UTM PhD student Dr. Aaron LeBlanc (now at the University of Alberta), Joseph Bevitt of ANSTO, Australia and Jun Chen of Jilin University, China.

Chinese bolosaurid Belebey, showing the replacement teeth in light blue growing beneath and in the pulp cavity of the functional teeth within the jaw.