Maneuverability in Mind and Memory

Do you vividly recall that red car your mom drove when you were a kid? Or that trip to the roller palace for your friend’s 8th birthday party a couple decades ago when you were wearing your favourite purple tracksuit?

These are details you might have stored in your long-term memory and a new study out of Psychology Professor Keisuke Fukuda’s lab indicates that “working memory,” which is typically associated with short-term memory, actually acts as a buffer for information retrieved from long-term memory.

Though researchers have long theorized we bring the information into working memory in order to retrieve it from long-term memory, Fukuda’s study helps to further prove this theory and to track this cognitive process in order to better understand the dynamics of memory retrieval.

“This idea may not sound surprising for those who have taken introductory cognitive psychology courses because it is so widely accepted that it appears in the related textbooks,” says Fukuda.

“What is surprising is that there hasn't been a clear demonstration that it actually happens in the brain.”

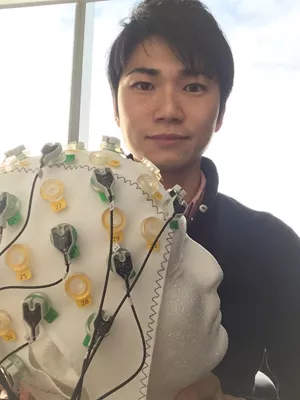

Through a series of three lab experiments where subjects first learned several different layouts of coloured squares each of which was associated with a specific alphabet, Fukuda and Professor Geoffrey Woodman, his collaborator at Vanderbilt University, employed electrophysiology technology to investigate the neural process in the brain when participants saw the alphabet and retrieved the layout of coloured squares from long-term memory. Their findings showed that long-term memory of the coloured squares were retrieved as the brain exhibited the same pattern of neural activities that support working memory. These findings bolstered the classic theoretical evidence that working memory is a conduit for information that is retrieved from long-term memory.

“Our finding is not just a neural demonstration of important theoretical concept about how our memory works, but what I think is most exciting is the discovery of a neural measure to observe how creative our mind is in manipulating mental images,” says Fukuda.

“For example, imagine seeing a real Pegasus. Although we have never seen a real horse with a pair of wings, our intuition tells us that we can retrieve the real image of a horse and a pair of wings from our long-term memory and put them together into one creature in our mind. We showed, by tracking the brain activity, that we could indeed do so!”

To read the full article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal, please see http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2017/04/26/1617874114.full.pdf.