Special exhibition showcases work of UTM palaeontology illustrator

As a child, Diane Scott struggled with reading, but a trip to the Etobicoke Bookmobile revealed that she had been reading the wrong books. Told to choose anything she wanted, the 7-year-old skipped the standard children’s stories in favour of an illustrated guide to human diseases. The book proved to be the gateway to literacy for the child, with a combination of science and images that helped to set the course for a research career that has spanned nearly four decades.

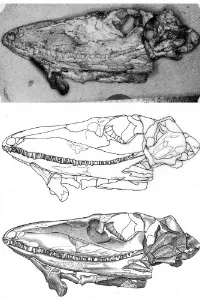

Since 1979, Scott has worked as a researcher and graphic artist, documenting paleontological discoveries at The Reisz Lab at U of T Mississauga. A retrospective of her illustration work opened in May at UTM in the offices of the Master of Biomedical Communications program.

Scott, who has no formal artistic training, earned her bachelor of science degree at Erindale College in 1980. Beginning as an undergraduate summer student, Scott soon demonstrated her unique talents for detailed technical work and accurate observational drawings.

“In this field, there are people who are artists and there are people who are technical preparators, but there’s only one Diane, who does both,” says biology professor and long-time collaborator Robert Reisz. “I don’t know of anybody else who does what she does.”

As a lab technician, fossil preparator and scientific illustrator, Scott is an anomaly. “I take the project from the beginning—I prep it, figure it out, draw it and reconstruct it,” she says. “I’m not a PhD or a post-doc. It’s very unusual for someone with my background to be allowed to do the things I do.”

Scott and Reisz have worked together for 37 years in what both describe as a true partnership. Scott has dozens of publications and hundreds of citations to her credit. “It’s a scientific conversation between Diane and myself,” Reisz says. “When I have a perspective, I have to prove it to her and she challenges me constantly. I drive the research, but Diane is the one who executes and carries forward the work.”

Once the specimen is prepared, Scott uses micromeasurements and her vast knowledge to reconstruct what the animal might have looked like. “You have to figure out where one bone stops and another begins. You have to look for clues to help identify what kind of an animal it is. Sometimes, it’s something new that we haven’t seen before,” she says. ”There’s no easy way of doing it.”

“As an illustrator, I’ve been impressed with how remarkable and beautiful these drawings are,” Mazierski says. “You can see from one to the next how Diane’s technique has evolved. It’s lighter in tone and more precise and more refined.”

“She plays with light and the forms that light and shadow create to make the drawing clear, but she bends the rules where it suits her,” Mazierski continues. “She’s most concerned about the form.”

Scott’s enthusiasm for her work is infectious. She describes the Massospondylus eggs as “the cutest things!” and has a soft spot for a small, beaked hippo-like creature called a Dicynodont. “If this thing existed now, it would be the number one pet,” she says.

“I never had to grow up,” Scott says. “I’m always learning. I’m never bored. I always liked art and I liked science and I get to do both every day.”

Visitors can view the exhibit from Monday to Friday between 8:30 and 4:30 in the Biomedical Communications hallway on the third floor of the Health Sciences Complex at the University of Toronto Mississauga until September 30, 2016.